Many Dungeons & Dragons and d20 System derivatives with a traditional class and level system tie skill improvement with level gain. This makes sense from a gameplay standpoint, especially when skills can affect surprise, sneak attacks, damage or have other play balance considerations. If you can advance your Deception skill(s) without limit, you can bypass enough challenges to derail almost any adventure.

These

optional rules are intended for use with such games and serve to provide a

greater sense of gradation with regard to character abilities by allowing character advancement to occur even without experience points, constant

adventuring, level-advancement and the potentially world changing levels of

power that can accompany them.

Why Level-Independent Skills?

The

inspiration behind these rules comes first from the skill advancement system

originating with RuneQuest

and second from the Epic

6

‘virtual rules set’ for Dungeons &

Dragons which were designed mostly with Dungeons

& Dragons 3.X and/or Pathfinder

in mind.

An article by Justin Alexander really drove this point home and explains how well the 3rd edition of Dungeons & Dragons works when you let go of the idea that all of the coolest characters of myth, legend and fantasy must be high level. The question then becomes, what happens after 6th level?

Of course, for some groups and campaigns, the magic number may not be 6. E8 and E10 games are also popular and every group has its own “sweet spot”. Regardless of what level represents your best play experience, most players still relish measurable advancement. With most E6 variants, characters gain new feats after acquiring a certain number of additional experience points, however this leaves aside another old idea from the earliest play experiences of the creators and codifiers of what we know as tabletop roleplaying. In the earliest versions of proto-D&D (as a supplement to Chainmail

Level-Independent Skills can be applied to games to reduce or remove the need to assign levels to NPCs or monsters simply to achieve a certain level of aptitude. As noted on the above Alexandrian blog article, the greatest minds of our non-epic world would top out at 5th level and could expect to achieve about +15 on very specialized skills, however should Einstein really have 5 hit dice? The article comments on hit points, but even built as a Commoner, our master physicist has a +2 base attack bonus and +1 to all saves.

In

addition, Level-Independent Skills allow for more dynamic character abilities.

Although advancing a level can be incredibly satisfying, seeing a character

suddenly and drastically gain new aptitudes after a metagame “ding” can stretch

the group’s sense of verisimilitude and feels very artificial. Being able to

improve skills, or see them degrade with lack of use, makes character abilities

appear more organic and can shift some focus away from what the player wants to

do upon leveling-up (“I’m going to take Draconic so I can read that scroll”) and

back towards what the character can or should do right now (“Can anyone in town

show me how to read these runes?”).

The

system below owes a great deal to HackMaster

(you could even call it a ‘hack’ of that system) and GURPS,

as well as Chaosium’s

Basic

Role-Playing, Call

of Cthulhu, Pendragon,

RuneQuest and the work of

Greg Stafford in

general.

Using Level-Independent Skills

Level-Independent

Skills typically have a rating between 1% and 100% but can go higher. Mastery

begins at a rating of 101% and normal characters cannot have a skill level greater

than 125%. Skill checks are percentile based and use a d100. After applying all

relevant modifiers the final result is compared to the character’s skill level.

If the result is equal to or less than the character’s skill level, the check

succeeds except that a result of ‘00’ always fails. Keep in mind that a skill

check is only called for under difficult conditions; if it wouldn’t make sense

for the character to fail, don’t call for a roll.

If

it is important to know how well a character performs a skill related task,

higher successful rolls represent a greater degree of success. Similarly, lower

failing rolls are less disastrous than higher ones. A character with a Skill

Level of 59% succeeds on a roll of ‘01’, but the success isn’t noteworthy while

a roll of ‘59’ means that the character achieved the absolute best result they

are capable of. If the player rolls a ‘63’ on a check for the same skill, the

character’s effort was good but the result came short of the mark. Perhaps they

attempted something a little too ambitious for someone at their level of

training.

Some

skills require a skill check so rarely that they serve primarily as a point of

comparison between characters. Cooking is a perfectly valid skill, however only

a very high standard or extremely

unusual circumstances would require a skill check. Still,

some players will be pleased when their character is recognized as the greatest

pastry chef in all the land.

Opposed Skill Checks

Opposed

skill checks occur when more than one character use skills in direct competition.

Each character involved makes a skill check. If more than one character

succeeds, the highest successful roll wins. If each character fails, the lowest

failing roll comes closest to success although this may be irrelevant depending

on the skill used and circumstances surrounding the check.

Most skills begin with a default skill level of untrained as determined by the ability score or scores most

relevant to the skill. If a skill doesn’t require special training and

effective use only relies on one ability score, the beginning skill level is

equal to that ability score.

For example, Hunting can be attempted by almost anyone and is a function of

Wisdom. Therefore, any character who could reasonably track game animals has an

untrained Hunting skill level equal to their Wisdom score.

If

two or more ability scores could affect the use of a skill, add all of those

scores together and divide by the number or relevant scores to determine a

character’s starting skill level.

Bartering relies on Charisma to convince the other party they are getting the best deal possible. Wisdom is equally relevant as a poor score may indicate that a character will misjudge the value of goods or services or else fail to notice an exaggeration or undue circumspection on behalf of the other party.

Bartering relies on Charisma to convince the other party they are getting the best deal possible. Wisdom is equally relevant as a poor score may indicate that a character will misjudge the value of goods or services or else fail to notice an exaggeration or undue circumspection on behalf of the other party.

In

this case, the starting skill level for Bartering is determined by adding

together the character’s Wisdom and Charisma, then dividing the result by two

(round down). Consequently, a Thief with Wisdom 11 and Charisma 8 has an

untrained Bartering skill level of 9%.

The gamemaster might decide that Bartering successfully also relies on Intelligence. If this is the case, assume the above Thief has an Intelligence of 14. This character’s Bartering skill would therefore begin at 11% (INT+WIS+CHA/3).

The gamemaster might decide that Bartering successfully also relies on Intelligence. If this is the case, assume the above Thief has an Intelligence of 14. This character’s Bartering skill would therefore begin at 11% (INT+WIS+CHA/3).

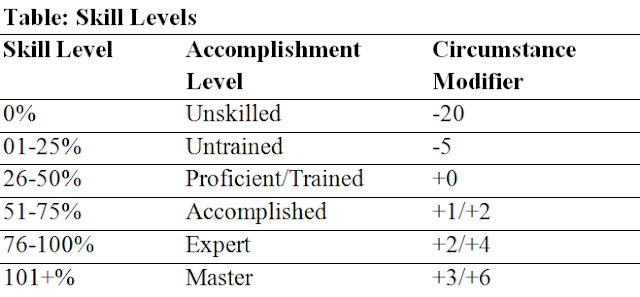

Unskilled, Trained, Accomplished,

Expert and Master Characters

Unskilled

characters have no faculty with the skill in question. This is the default

skill level for any skill that requires training. A character with this level

in a skill has a 0% chance to succeed when attempting it. An exception can be

made if a trained character is able to provide direct instruction. In this

case, the attempt will only succeed on a result of ‘01’ unless there are

favorable modifiers to apply.

Trained

characters probably use their skill on a daily basis and can earn a living with

it. Accomplished characters are

highly dedicated to maintaining and improving the skill in question. Such characters

are able to train others in the use of the skill. Expert and Master characters

are both passionate about the skill and are very likely to look for

opportunities to teach it to others or to seek the recognition of other

practitioners. Masters are exceedingly rare and are likely to be well known,

even by lay-persons, over a wide region.

Learning and Maintaining Skills

Skill

Levels can be improved during the character generation process, as well as

through and regular use. Each skill possesses the attributes which influence a

character’s ability to learn them: rate of progression;

learning difficulty; and suggested cost. Some skills also have prerequisites which must be met before

the skill can improve.

A

skill’s rate of progression is represented by a die type, usually d4, d6, d8 or

d10. When a skill improves, roll the appropriate die and add the number shown to

the character’s skill level. Very basic or easy to learn skills may use d12 or

d20. Only very demanding skills use 1d4.

Learning

difficulty is used only when the gamemaster requires a check to improve a skill

(see Improving Skills below). Easy skills lower the difficulty of the check

while harder skills increase it. If the check is made using a d20 the learning difficulty

value provides a modifier of +/-0 to +/-5. If the check is made using d100, add

or subtract between 0% and 25%.

The

suggested cost of a skill is the price of one week of formal instruction in the

use of it. The base cost should be determined by how difficult the skill is to

learn, how much demand there is for it to be taught, and how expensive any training

aids used might be. Some very basic skills may not be available for formal

training as characters are assumed to be able to learn what they need to know

on their own, perhaps during childhood. In this case, the cost for training

would need to be worked out on a case by case basis.

If

a skill has any prerequisites, the character must meet them before attempting

to learn or improve a skill. Some skills could have an ability score

prerequisite, although this is rare. Other skills may be prerequisites for more

specialized ones. If this is the case, the character must have a skill level of

50% or more in any prerequisite skills before training.

Starting Skill Levels

How

skill acquisition is represented and adjudicated for starting characters depends

greatly on the game system and number of skills used. For example, Pathfinder has a fairly concise set of skills

and access to skills is a function of each character’s class and Intelligence. GURPS has a huge list of potential skills depending on the level

of detail desired. Games like Advanced

Dungeons & Dragons and Call of

Cthulhu fall somewhere in the middle while others have no skills at all.

Consider

these options:

•Proficiencies

or Skill Points: For each proficiency slot or skill point, the character gains

one skill at a skill level of 50% plus the relevant ability score. These

systems tend to assume a high level of competence with a character’s chosen

skills and this method results in characters with a small set of skills with

which they are considered accomplished.

•Character/Build

Points: Some systems assign a point cost to multiple aspects of character

creation, often including talents, powers, skills and more. These systems tend

to use greater detail with regard to skills and may already have an approach to

skills that takes into account the difficulty of learning certain skills

compared to others. Some use the skill’s perceived gameplay value to establish

cost; Stealth might cost more than Cobbling for instance. Other systems focus

on realism and assign higher costs to more difficult or obscure skills. In

either case, the gamemaster will need to assign a point cost to each skill and

a character’s skill improves by its progression rating each time the player

pays that cost during character creation.

Improving Skills

Characters

usually improve skill levels after character generation by training. This can

take a variable amount of time depending on the skill and quality of training,

but generally should take between 1 week and 1 month of dedicated study

assuming an 8 hour training session per day.

After

completing a course of study, the character’s skill level improves according to

its progression rating. If you wish to make skill improvement less certain, use

an Intelligence check or “Learning” check modified by the skill’s difficulty. In

this case, a character can continue to train the skill for another week and then

make another check with a +1 (or +5%) bonus to their check until they succeed

or leave their training behind.

The following types of training are available and may modify the required training time:

The following types of training are available and may modify the required training time:

Formal Training:

The character has access to a qualified instructor and training materials. Training

time is unmodified. If using a check to determine success with training, you

may assign a bonus or penalty based on the quality of the instructor.

Informal Training: The character either studies independently to improve their skill or receives mentoring from another character with a higher skill level. Independent study doubles the amount of time required to improve a skill.

Informal Training: The character either studies independently to improve their skill or receives mentoring from another character with a higher skill level. Independent study doubles the amount of time required to improve a skill.

Mentoring

takes up the usual amount of time, however the mentor should make a skill check

at the end of the training period. If the check fails, the training time is

wasted and the student can only improve this skill in the future by completing

at least one formal training course.

On-Task Training:

While working or performing other skill related tasks, characters can improve related

skills. The skill to be improved must be one that the character uses at least

50% of the time during the course of their work. Since the character’s

attention is generally focused on completing tasks using tried methods,

multiply the training time required by at least four.

Keep in mind that some duties aren’t conducive to training. A guard might primarily use Observation while keeping watch, but most of the time spent at this task is probably just walking around and occasionally scrutinizing an out of place person or sound. It’s doubtful that this would meet the criteria for 50% skill use while on duty.

Keep in mind that some duties aren’t conducive to training. A guard might primarily use Observation while keeping watch, but most of the time spent at this task is probably just walking around and occasionally scrutinizing an out of place person or sound. It’s doubtful that this would meet the criteria for 50% skill use while on duty.

Spontaneous Improvement:

At the gamemaster’s option, it may be possible for a character to improve a

skill when putting forth their best effort under extreme conditions. When a

skill check is called for and the character is involved in a stressful

situation, a small chance exists that the character will gain special insight

into the skill being used. If the skill check result (after any modifiers) is

equal to the chance of success, the character may have learned something from

the experience.

At the beginning of the next adventure or game session, the player should roll 1d100. If the result is higher than the character’s skill level, increase it according to the progression rating for that skill. If the skill level is 100 or more, the skill improves only on a roll of ‘00’ and only by 1 point.

At the beginning of the next adventure or game session, the player should roll 1d100. If the result is higher than the character’s skill level, increase it according to the progression rating for that skill. If the skill level is 100 or more, the skill improves only on a roll of ‘00’ and only by 1 point.

If

characters don’t use their skills, they will degrade over time. Players should

add a check mark next to a skill under the following circumstances: The

character receives at least 8 hours (1 day) of formal training in the skill; the

character performs at least 16 hours (2 days) of independent study in the skill;

the character performs skill related work for at least 32 hours (4 days); or the

character succeeds on a skill check the gamemaster called for during an

adventure.

At the end of one month, each skill without a check beside it should degrade by one point.

At the end of one month, each skill without a check beside it should degrade by one point.

Since this added bookkeeping may not appeal to some groups, skill maintenance is optional.

Weapon Skills

With

Level-Independent Skills, weapons are handled differently than in most games.

As with other skills, weapons have a skill level which indicates a character’s

level of training, however if combat is not resolved with skills checks in your

game system the training level is primarily used to determine if the character

receive a bonus or penalty to attacks with the weapon as indicated by the

circumstance modifiers on the Skill Levels table.

The gamemaster should decide whether to use the number before or after the slash for the indicated accomplishment level. Generally, the lower number should be used if there are a number of other factors contributing to combat abilities aside from skills such as class-based attack bonus, optional talents and feats, superior equipment, and so on. If fewer (or smaller) modifiers are the norm, use the higher listed modifier.

If skill is the only major contributing factor in a combat scenario or other situation (such as target shooting), you can use weapon skill checks to resolve attacks and apply the circumstance modifier to damage rolls.

The gamemaster should decide whether to use the number before or after the slash for the indicated accomplishment level. Generally, the lower number should be used if there are a number of other factors contributing to combat abilities aside from skills such as class-based attack bonus, optional talents and feats, superior equipment, and so on. If fewer (or smaller) modifiers are the norm, use the higher listed modifier.

If skill is the only major contributing factor in a combat scenario or other situation (such as target shooting), you can use weapon skill checks to resolve attacks and apply the circumstance modifier to damage rolls.

See

below for more details on using skills to resolve combat.

Starting Weapon Skills

In

games with weapon proficiencies or slots, starting characters may select the

indicated number of weapon skills at a skill level of 50% plus the relevant

ability score (as with other skills). For games with build points, the cost of

a particular weapon skill should usually be equal in cost to ‘average’ skills

except for rare or especially unwieldy weapons.

This

system assumes that weapon skills represent a group of similar weapon types. Examples

include: Axes and maces; Bows; Firearms; Short blades and sticks; or Whip. The

gamemaster should decide if more or less detail is required and adjust costs accordingly.

Firearms might be too broad for some games and can be subdivided into Pistols,

Rifles and Shotguns. For other settings, large sets of diverse weapons can be grouped

together under one skill at a higher cost such as “Thief weapons” or “Monk

weapons”.

Most

weapon skills can be used without training at a skill level equal to the

relevant ability score, but if a character his little understanding of the

technology behind a weapon or otherwise eschews the use of such a weapon, they

may begin with an accomplishment level of unskilled (0%).

In

Dungeons & Dragons for example, Clerics

often begin with 0% skill mastery in all weapon skills except for blunt weapons

or those preferred by the character’s deity. Likewise, if the technology level

of the setting is “medieval” characters native to the setting will be unskilled

with firearms or alien blasters.

Skill Checks and Combat

As

noted above, weapon skill levels can influence combat, however in a class and

level system skill use is not usually the primary determining factor. If the

gamemaster decides to use weapon skill checks as a measure of combat effectiveness,

skill modifiers will need to be applied to represent defensive capabilities,

terrain features and other circumstances.

For

example, if combat is normally resolved using a d20 and a shield provides a +2

defense bonus, this adjustment can be handled as a -10% penalty on the attacker’s

weapon skill check. Another option is to include a Shield or Block skill and

make use of opposed checks. In this case, the attacker makes a weapon skill

check and the defender makes an opposed Block skill check.

Parries can be resolved with opposed weapon skill checks. The defender’s skill check should be modified if the weapon is difficult to parry with (like a flail) or if it is much smaller or lighter than the attacker’s weapon.

Parries can be resolved with opposed weapon skill checks. The defender’s skill check should be modified if the weapon is difficult to parry with (like a flail) or if it is much smaller or lighter than the attacker’s weapon.

When

using skills to resolve combat, there should be a limit to how many times a

character can block or parry, perhaps half the character’s Dexterity score.

Games with a fixed defense score (where the attacker must roll over a certain

number to hit) assume an average defensive value which doesn’t degrade when

fending off multiple attacks. To simulate this, you can halve the defender’s

defensive skill level any time they face more than one attack. Otherwise,

consider assigning a penalty for each attempt at defense after the first.

Ranged

attacks can usually be blocked (unless the missile moves very quickly), but not

parried. Instead, characters should have a Dodge chance to avoid ranged attacks.

This can be treated as a skill of its own or may be a fixed score based on

Dexterity or some other statistic. Of course, special abilities or weapons may

grant the ability to parry ranged attacks.

Even

the gamemaster doesn’t wish to use skills to resolve combat, weapon skill

checks can be used either to perform feats of skill with the weapon. They can

also be used to quickly resolve brawls or other challenges that are trivial to

the adventure or campaign.

Skills and Luck

When

using Luck

as an optional ability score, the gamemaster should decide how it affects

starting skill levels and skill use. Luck could be considered a relevant

ability score for all skills and therefore

every skill is based on Luck plus one or more other abilities. The Bartering

skill might then have a starting level of (INT+WIS+CHA+LUCK/4).

It could also be that Luck only influences certain skills (as determined by the character’s birth sign described in the Luck article) or that it applies a modest adjustment to all skills such as plus or minus a percentage point equal to the character’s Luck modifier.

It could also be that Luck only influences certain skills (as determined by the character’s birth sign described in the Luck article) or that it applies a modest adjustment to all skills such as plus or minus a percentage point equal to the character’s Luck modifier.

No comments:

Post a Comment